Effectiveness of Animal-assisted Therapy a Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials

Abstruse

Objectives

Animal-assisted therapy with dogs is regularly used in children with behavioural and developmental disorders. Aims of this systematic review were threefold: to analyse the methodological quality of studies on canis familiaris-assisted therapy (DAT) for children with behavioural and developmental disorders, to decide to which extent the studies on DAT adhere to the quality criteria developed past the International Association of Human being Beast Interaction System (IAHAIO) and to describe the characteristics of the participants, the intervention and the outcomes.

Method

Three databases (i.e. PsycInfo, MedLine and Eric) were searched, and xiv studies on DAT were included. The Joanna Briggs Constitute checklist (JBIC) and the quality criteria developed by the IAHAIO were used during data extraction. Characteristics of the participants, the intervention, the therapy dogs and the outcomes of the studies were summarised.

Results

Six of the 14 included studies reported significant outcomes of DAT, whereof half dozen in the social domain and two in the psychological domain. However, scores on the JBIC indicated depression to moderate methodological quality and only 3 of the included studies adhered to the IAHAIO quality criteria.

Conclusions

DAT is a promising intervention for children with behavioural and developmental disorders, especially for children with autism spectrum disorder. A clear description of the therapy'south components, the role of the therapy domestic dog and analysis of the treatment integrity and procedural fidelity would better the methodological quality of the studies and the field of dog-assisted interventions.

The growing body of literature indicates that fauna-assisted therapy (AAT) with dogs is a promising intervention for children with different types of behavioural and developmental disorders (Hoagwood et al., 2016; Schuck et al., 2018). In AAT, an animal is present during a therapeutic intervention together with the client and the therapist, and it is used to improve the social skills of the client, to reduce psychological symptoms and/or to promote neurobiological processes (Gut et al., 2018; Jegatheesan et al., 2018). Given their ability to adapt to human being behaviour, read and react to human (body) language, availability and trainability, dogs are ane of the most common animals used in AAT (Duranton & Gaunet, 2018; Glenk, 2017; Miklósi & Topál, 2013). In a recent written report from Kerulo et al. (2020), the perspective of 239 professionals working in the field of animal-assisted interventions (AAI) was investigated, and it was found that most professionals (88%) were working with dogs.

During therapeutic interventions, dogs can be integrated in an active or passive way. In a study by Hill et al., (2019a, 2019b), dogs were integrated in either an active or a passive way depending on the needs and goals of the client. For example, children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder were working actively with the dog, playing catch to strengthen the contained functioning of the child, while other children were working passively with the dog, learning how to recognise emotions. Likewise, passive AAT programmes for children to heighten their reading skills are commonly used in libraries and schools (Henderson et al., 2020). While the child is reading, the dog is sitting or lying next to the child without further interaction. Another stardom oft made in AAT is that the dogs are integrated into individual therapy or group therapy. For case, Wohlfarth et al. (2013) investigated the motivational effects of the active use of dogs in groupwise training for obese children, while Griffioen et al. (2019) studied the changes in synchronicity between children and dogs during individual therapy sessions. A further distinction can be found in the setup of the therapy session. In some studies, AAT is provided by a therapist who is responsible for both providing therapy to the client and treatment the domestic dog (eastward.g. Wijker et al., 2019). In other studies, a therapist provides the therapy simply is assisted by a dog handler who is responsible for ensuring the welfare and safe of the dog (eastward.g. Flynn et al., 2018; Hediger et al., 2019). Also, training and certification of the therapist, handlers and dogs differed across studies.

During the past decade, several attempts have been fabricated to summarise the effectiveness of AAT in children and adults, including children with autism spectrum disorder (Fung & Leung, 2014), adults with autism spectrum disorder (Wijker et al., 2021), children with pervasive developmental disorder (Martin and Farnum, 2002), children with Down's syndrome (Griffioen et al., 2019), children who were sexually abused (Dietz et al., 2012) and children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Juríčková, et al., 2020). Beetz et al. (2021) categorised the outcomes of DAT as (i) improvements in social skills such as empathy and communication (Hill et al., 2019a, 2019b; Stevenson et al., 2015; Wells et al., 2019), (2) psychological effects such equally improvements in concentration and motivation (Busch et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2019a, 2019b; Schuck et al., 2013, 2018) and (3) neurobiological effects such as decreases in heart charge per unit and claret pressure (Nagasawa et al., 2015). While near studies on AAT focussed on the effectiveness of dog-assisted therapy (DAT), studies systematically investigating the therapy approaches, settings and inquiry methodology are scarce (Fine et al., 2019).

In line with the rapid increase of AAT providers, several organisations, including Pets Partners, the International Clan of Man Animal Interaction Organisation (IAHAIO), Animal Assisted Intervention International and the International Society for Animal Assisted Therapy, were founded to protect and ensure the welfare and wellbeing of the clients, therapists and animals participating in AAT. These organisations have introduced several guidelines for healthcare interventions, including the part and wellbeing of animals. Although these guidelines are regularly used in clinical practice, lilliputian is known almost how these are practical in current and past AAT studies. Therefore, the aim of this review is threefold. First, we apply the Joanna Briggs Constitute checklist (JBIC) to analyse the methodological quality of the studies evaluating DAT in children with behavioural and developmental disorders. Second, we investigate to which extent studies on DAT adhere to the AAT quality criteria developed by the IAHAIO. And third, nosotros summarise the characteristics of the participants, intervention, therapy dogs and outcomes of the studies.

Method

Procedure

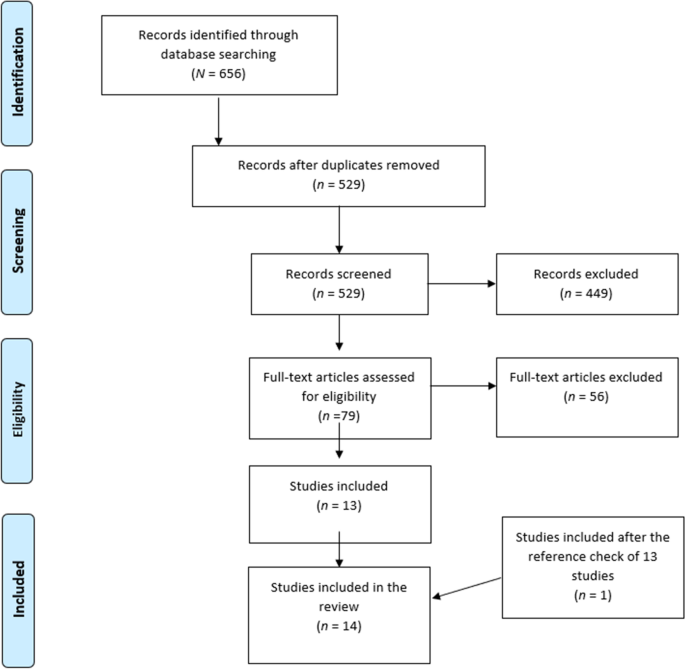

Three databases (i.e. PsycInfo, MedLine and Eric) were searched, combining standard terms used in children with behavioural and developmental disorders and AAT with dogs to identify studies (encounter Fig. i for the selection process). Two academic librarian were consulted to develop the post-obit search strings: (Child* or adolescent* or baby* or toddler* or student* or pre-schooler* or puber*) AND (therap* or intervention* or coach* or activit* or consult* or preparation or education or learning or handling* AND (domestic dog* aid* or assis* dog* or domestic dog* based or canis or kanis or (therap* adj3 domestic dog*)) OR (animate being* help* or assist* fauna* or brute* based or animal*) OR (trained domestic dog* or therapy dog* or service dog*) OR (domestic dog* assist* or assis* domestic dog* or dog* based or canis or kanis or (therap* adj3 dog*)). The search was limited to include just studies published betwixt 2008 and 2020 in peer-reviewed journals and published in English language (i.due east. 6 years before and 6 years subsequently the publication of the IAHAIO guidelines; Jegatheesan et al., 2018). Duplications were removed, which resulted in 529 studies. Next, the showtime and second authors screened all titles and abstracts for the four inclusion criteria, which were based on the PICO criteria (Higgins et al., 2019): (ane) participants were children betwixt 0 and xviii years of age; (ii) a dog was included in the intervention; (3) the interventions were implemented in a therapeutic setting with a healthcare professional, a therapeutic goal and multiple individual therapy sessions; and (4) furnishings of the interventions on the participants were measured. As pointed out by Chandler (2017) and Seivert et al. (2016), a close human relationship between a therapy dog and customer is an essential component of DAT. Therefore, we only evaluated individual therapy sessions in this review. Differences between the authors were discussed until consensus was reached.

Prisma flow chart of data extraction

Later on the pick process, xiii studies were identified, and the references of these 13 studies were checked for relevant studies. 1 written report that met the inclusion criteria was identified and also included in the review. This resulted in a full of fourteen studies that were analysed past the first author. The 2d author analysed three (21%) of the included studies. Hill et al., (2018; 2019a, b) described the same research project from unlike perspectives; these studies were treated every bit one study. During the selection procedure, interrater reliability between the first and second authors was calculated, using Cohen's M for evaluating the agreement between raters (Cicchetti, 1994). Substantial agreement between the first and second authors was found, One thousand = 0.66, p < 0.001 (McHugh, 2012).

Data Analysis

Two forms were used during information extraction. First, the JBIC was used to analyse the quality of the studies according to the current standard for intervention studies. Second, a customised form based on the PRISMA extraction class and IAHAIO Whitepaper was used to evaluate to which extent studies adhered to the quality guidelines of the IAHAIO and to draw the outcomes of the studies. The start author extracted the data of all studies. In addition, the second author analysed three of the included studies to summate interrater agreement. Substantial understanding was establish, K = 0.61, p < 0.001 (McHugh, 2012).

Quality of the Studies

The Joanna Brigg Constitute checklists (JBIC) for Example Studies (Moola et al., 2020), Qualitative Research (Lockwood et al., 2015), Quasi-Experimental Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials (Tufanaru et al., 2020) were used to evaluate the quality of the study relative to research standards for interventions studies. The JBIC contains dissimilar checklists, which measure the methodical quality and risks of bias of the studies (Ma et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2019). Depending on the report format, the matching checklist of the JBIC was used. By answering 8 to thirteen closed-concluded questions (depending on the type of written report pattern reviewed past the checklist), the JBIC evaluate the quality of the written report design, completeness of the information on the participants and enquiry methods used. The JBIC were chosen considering of their availability for all four types of studies covered in the present review and its up-to-dateness. The results are presented in percentages of abyss based on the number of criteria with a range from 0 (data is not described) to 100 (all information is bachelor and described).

AAT Quality Criteria and Outcome

A customised data extraction form was used to excerpt data related to the IAHAIO criteria and outcomes of the studies. The form was based on the PRISMA checklist and the IAHAIO Whitepaper (Jegatheesan et al., 2018). The PRISMA was called to ensure complete and transparent information extraction (Liberati et al., 2009), while the IAHAIO Whitepaper was used to operationalise AAT and as a guideline for the adequate treatment of human and dog welfare during the interventions. The course consisted of three components: (ane) characteristics of the participants (i.e. gender, historic period and diagnosis), (2) characteristics of the domestic dog (i.east. breed, gender, age, color, neutered/meaning, owner) and (iii) result variables (see Table ane).

Results

The Current Standard for Intervention Studies

Of all fourteen studies, 9 used a quasi-experiment blueprint, and 3 used a randomised control trial design. Also, i instance study and 1 qualitative study were included. The qualitative study had the highest quality score on the JBIC, with 90% of the criteria completed. The 3 randomised controlled trials scored on average 74% (range: 69–77%). The studies that used a quasi-experimental design (due north = ix) had a hateful score of 62% (range: 44–78%), and the case study had the lowest score with 50% of the criteria completed on the JBIC. According to the JBIC criteria, virtually studies reported sufficient information near the participants. Withal, only 6 studies used a control group. Virtually control groups received a similar treatment equally the experimental group only without a domestic dog, making blinded rating difficult. The JBIC scores of the individual studies can be constitute in Tabular array two.

AAT Quality Criteria

To assess to which extent the studies adhered to the AAT quality criteria (Jegatheesan et al., 2018), the characteristics of participants, dogs, professionals and intervention were summarised showtime.

The number of participants ranged from 1 to 117. Information technology included children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (11 of the 14 studies), children in paediatric care (2 studies), incarcerated youth (1 study) and participants with Downwardly syndrome (two studies). 1 of the latter two studies included both children with autism spectrum disorder and Down syndrome. The age of the participants ranged from four to xix years, and most participants were boys (seventy%). The therapeutical orientation was mentioned in six studies, including occupational therapy (2 studies) and applied behaviour assay (1 report). Characteristics of the studies are summarised in Tabular array 2.

In the xiv studies, betwixt one and eleven dogs were used. In line with the IAHAIO-criteria, the studies were screened on the following 6 characteristics of the dog: (1) breed, (2) gender, (3) historic period, (4) colour, (5) neutered/significant and (6) and dog-possessor (see Tabular array 2). In near studies, information regarding the characteristics of the dogs was deficient. Of the half-dozen characteristics, near studies reported fewer than three, with an average of 2.v characteristics. In half dozen studies, a triadic setting (i.e. canis familiaris, child and therapist) was used, while in five studies, a dog handler was added, and a quadratic setting was used (i.due east. dog, dog handler, child and therapist). In three studies, this data was not reported.

In the IAHAIO Whitepaper, nine criteria are identified to protect the welfare of the participants and the dogs (Tabular array i). The first three criteria focussed on the welfare and background of the participants and the other half-dozen on the welfare, training and handling of the domestic dog. All studies reported information on i or more of the kickoff three criteria that were related to the welfare and background of the participants. Eight studies reported that participants were checked on dog-related allergies, and in 12 studies, the education of the therapist who provided AAT was reported. But one study reported the cultural groundwork of the participants. Most studies reported scarce information on the six criteria related to the characteristics and welfare of the dog (i.e. breed, gender, age, colour, neutered/pregnant and owner). The most shared information about the therapy dogs was that they are socialised (ten/14), registered equally therapy dog (9/fourteen), evaluated (vii/14) and veterinary checked (v/14). Twelve studies also reported that the therapist and/or dog handler were educated and certified in dog training and/or handling. All studies reported the duration of the sessions. However, most studies did not written report brood, color, age or gender and also five of the 14 studies described therapy sessions with a longer elapsing (i.e. 60 min) than prescribed in the IAHAIO criteria (i.eastward. 30–45 min).

Simply 3 studies adhered to all AAT criteria, seven did not attach to the criteria. Four studies reported insufficient information to assess if AAT criteria were followed. Of the three studies that adhered to the guidelines, two were published before the publication of the guidelines (Jegatheesan et al., 2018). Of the eight studies that were published afterwards the publication of the AAT criteria, simply one written report was designed in line with these guidelines. Although 2 studies referred to the IAHAIO guideline, both studies did not run across the criteria. Just five studies reported that a handling protocol or manual was used.

The Outcome of the Studies

To evaluate the outcomes of the studies, the data were summarised and categorised into three domains. Table two depicts the outcomes on the 3 domains of effectiveness proposed by Beetz et al. (2021): social, psychological and neurobiological. Near studies (78%) reported outcomes on the social domain, including increased social and communication skills and reduction in aggressive behaviours. Ten studies (71%) reported psychological outcomes, including more than motivation and concentration. Only one study evaluated the neurobiological outcomes of DAT and institute reductions in salivary cortisol levels in five children (Protopopova et al., 2020). Six of the 14 studies (43%) reported meaning outcomes of DAT, whereof six in the social domain and 2 in the psychological domain. Well-nigh studies also reported anecdotal outcomes such equally improved motivation or reduction of aggressive behaviour.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the methodological quality of studies investigating DAT in children with behavioural and developmental disorders and the extent to which these studies adhered to quality guidelines of IAHAIO (Jegatheesan et al., 2018). Besides, characteristics of participants, intervention, therapy dogs and outcomes were summarised. The quality of the 14 included studies was evaluated using two checklists. The overall methodological quality of the studies was evaluated using the JBIC, and the criteria of the IAHAIO were used to appraise if studies adhered to the guidelines for human and animal welfare in AAT. Xl-four to 90% of the criteria of the JBIC were met, which is in line with other studies that assessed the methodological quality with the JBIC. For case, Kanninen et al., (2021) evaluated interventions for strengthening professionals' governance in nursing in hospitals and found that 55 to 89% of the criteria were met. Xiao et al. (2019) reviewed studies on the outcome of therapy on nobility, psychological wellbeing and quality of life among cancer patients. With 62 to 89% of the criteria met, none of the studies included in their review fulfilled all JBIC criteria (Xiao et al., 2019). JBIC scores of the 14 included studies indicated depression to moderate methodological quality.

While in well-nigh studies all JBIC criteria regarding the participants were met, criteria regarding the randomisation and blinding of the assessors were non met. Furthermore, it was difficult to extract data related to the intervention as many studies did not report sufficient information regarding the intervention and command conditions. Often, no information regarding theories underlying the intervention, the handling protocol, and intervention techniques was given, and handling integrity and procedural fidelity were often not measured. Included studies were characterised by a high degree of heterogeneity regarding the participants, the intervention and the control weather used. Although all studies investigated DAT, the number of sessions varied from 4 to 37 and duration of the sessions varied between 5 and 60 min. Besides, the therapeutic function and tasks of the therapy canis familiaris differed across studies. While in the study of Seivert et al. (2016) the interaction between the dog and the child was integrated into the therapy programme, Protopopova et al. (2020) used the therapy dog as a reinforcer for the participation of the child in an educational job. Most studies provided picayune information on the treatment and the procedures related to the canis familiaris's part in the treatment and setting of the treatment. No report measured the long-term effects of DAT.

The IAHAIO is the global association of organisations that engage in AAI. Their criteria for AAI outline the best practices in delivering DAT to ensure the health and wellbeing of both clients and therapy dogs. As these criteria are seen equally the golden standard in clinical do, they were used to evaluate the quality of DAT provided in the included studies. As no clear definition, description and protocol of DAT exist, recommendations of the IAHAIO were summarised based on 9 criteria to evaluate the quality of the intervention. Unfortunately, interventions often did not adhere to these criteria or information related to these criteria was defective, making it incommunicable to determine if studies adhered to the criteria. For case, the criteria state that sessions should be time-express (xxx–45 min) to forestall the dogs from becoming overworked or overwhelmed. Yet, five of the 14 studies reported sessions longer than 45 min (Hill et al., 2019a, 2019b; Jorgenson et al., 2020; London et al., 2020; Seivert et al., 2016; Vitztum et al., 2016). In addition, AAI should but be performed with the help of animals in good health, well-socialised with humans and trained adequately with humane techniques (Jegatheesan et al., 2018). While Seivert et al. (2016) referred to the IAHAIO criteria, they used dogs from an animate being shelter. These dogs had behavioural issues such as jumping and pulling and lacked socialisation. Oft, characteristics of the dogs, such as their age or veterinarian checks, were not reported, making it difficult to conclude if studies adhered to the IAHAIO criteria.

The therapy dog is a crucial element in DAT. Articulate protocols are needed to ensure the wellbeing and rubber of clients, therapists and dogs (Jegatheesan et al., 2018) and to operationalise DAT further. However, little information on the dogs was provided in the current studies. Just some studies provided some data almost the dog'south characteristics, the dog's role during the therapy session and the treatment location and materials. For example, the canis familiaris can be used to reinforce the social behaviour of a child instead of using edible and/or social reinforcers provided by the therapist (Protopopova et al., 2020). Still, the dog can as well participate and collaborate with the child during a job or exercise (Hill et al., 2019a, 2019b). While characteristics of the dogs, such as breed and color, might influence the effectiveness of DAT, most studies lacked data on these characteristics. For example, color differences might influence the outcomes of DAT. Lavan and Knesl (2015) showed that black dogs remained longer in shelters than dogs with other colours because black dogs await more than menacing and are more hard to read during interactions. It is essential to written report these characteristics to compare outcomes between studies and learn more than about the effect in DAT.

7 of the xiv studies identified significant effects of DAT. Furthermore, in the qualitative study, parents and therapists reported that children were more engaged, showed more than enjoyment, and were more motivated in the therapy domestic dog'south presence (London et al., 2020). In add-on to the quantitative outcomes, many studies reported anecdotal outcomes, such equally increased motivation and decreased aggressive behaviour (London et al., 2020). Since most of these studies did not measure increased motivation and decreased ambitious behaviour, future studies should investigate these effects using valid and reliable measures and study designs.

Limitations and future research

Although the findings of the present review show that DAT is a promising intervention for children with behavioural and developmental disorders, the results too emphasise that more robust research methods are warranted to strengthen the electric current cognition base of operations. To further accelerate the field, time to come studies must include a clear clarification of the handling components and the office of the therapy dog in the intervention. Too, the context wherein DAT is provided should be clearly described to enhance the replicability of the results. Therefore, clear guidelines need to exist developed that describe the characteristics of participants, therapy dogs and interventions that should be reported in interventions studies with animals. Equally treatment integrity and procedural fidelity of DAT were often not assessed and different outcome measures were used, information technology is not piece of cake to compare and generalise the results between studies. Time to come studies should include measures on treatment integrity and procedural fidelity and measures to evaluate the brusk-term and long-term effectiveness of DAT. As several studies reported anecdotal outcomes such every bit improved motivation or reduction of aggressive behaviour, future studies should include measures on these outcomes. Furthermore, qualitative studies should analyse the experiences reported by therapists and children, while observational written report designs could be employed to get more insight into the underlying theories and working mechanisms of DAT. These findings may be limited considering the information needed to analyse the IAHAIO criteria was defective in some studies.

References

-

Barker, South. B., Knisely, J. Southward., Schubert, C. G., Light-green, J. D., & Ameringer, Southward. (2015). The effect of an creature-assisted intervention on anxiety and pain in hospitalized children. Anthrozoös, 28(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279315x14129350722091

-

Beetz, A., Wohlfarth, R., & Kotraschal, K. (2021). Tiergestützt intervention [Animal assisted intervention] (Vol. 2). Ernst Reinhardt GmbH & Co.

-

Busch, C., Tucha, L., Talarovicova, A., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Lewis-Evans, B., & Tucha, O. (2016). Animal-assisted interventions for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychological Reports, 118(1), 292–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294115626633

-

Chandler, C. Grand. (2017). Animal-assisted therapy in counseling (3rd ed.). Routledge.

-

Cicchetti, D. V. (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, half dozen, 284–290. https://doi.org/ten.1037/1040-3590.6.four.284

-

Dietz, T. J., Davis, D., & Pennings, J. (2012). Evaluating animal-assisted therapy in grouping treatment for child sexual corruption. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 21(6), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2012.726700

-

Duranton, C., & Gaunet, F. (2018). Behavioural synchronization and affiliation: Dogs showroom human-like skills. Learning and Behavior, 46(four), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13420-018-0323-4

-

Fine, A. H., Beck, A. M., & Ng, Z. (2019). The State of animal-assisted interventions: Addressing the contemporary issues that will shape the futurity. International Journal of Ecology Inquiry and Public Health, 16(20), 3997. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203997

-

Flynn, E., Roguski, J., Wolf, J., Trujillo, K., Tedeschi, P., & Morris, Grand. North. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of animal-assisted therapy as an adjunct to intensive family preservation services. Child Maltreatment, 24(ii), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559518817678

-

Funahashi, A., Gruebler, A., Aoki, T., Kadone, H., & Suzuki, K. (2013). The smiles of a child with autism spectrum disorder during an animal-assisted activity may facilitate social positive behaviors: Quantitative analysis with grinning-detecting interface. Periodical of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(3), 685–693. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s10803-013-1898-4

-

Fung, S. C., & Leung, A. S. M. (2014). Pilot study investigating the role of therapy dogs in facilitating social interaction among children with autism. Periodical of Gimmicky Psychotherapy, 44(four), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-014-9274-z

-

Glenk, L. (2017). Current perspectives on therapy dog welfare in animal-assisted interventions. Animals, 7(12), 7. https://doi.org/ten.3390/ani7020007

-

Griffioen, R. E., Steen, S., Verheggen, T., Enders-Slegers, M., & Cox, R. (2019). Changes in behavioural synchrony during dog-assisted therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder and children with Down's syndrome. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(3), 398–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12682

-

Grigore, A. A., & Rusu, A. Due south. (2014). Interaction with a therapy dog enhances the effects of social story method in autistic children. Society & Animals, 22(3), 241–261. https://doi.org/x.1163/15685306-12341326

-

Gut, W., Crump, L., Zinsstag, J., Hattendorf, J., & Hediger, K. (2018). The upshot of human interaction on guinea pig behaviour in animal-assisted therapy. Journal of Veterinarian Behavior, 25, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jveb.2018.02.004

-

Hediger, M., Thommen, S., Wagner, C., Gaab, J., & Hund-Georgiadis, M. (2019). Effects of animal-assisted therapy on social behaviour in patients with acquired brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Scientific Reports, 9(one), 5831. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-42280-0

-

Henderson, 50., Grové, C., Lee, F., Trainer, 50., Schena, H., & Prentice, M. (2020). An evaluation of a dog-assisted reading program to support educatee wellbeing in principal schoolhouse. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105449

-

Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, 1000., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, Five. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Wiley Cochrane Series) (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

-

Colina, J., Ziviani, J., Cawdell-Smith, J., & Driscoll, C. (2019a). Canine assisted occupational therapy: Protocol of a pilot randomised control trial for children on the autism spectrum. Open Journal of Pediatrics, 9(3), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojped.2019.93020

-

Hill, J., Ziviani, J., Driscoll, C., & Cawdell-Smith, J. (2018). Can canine-assisted interventions bear upon the social behaviours of children on the autism spectrum? A systematic review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(one), xiii–25. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s40489-018-0151-vii

-

Hill, J., Ziviani, J., Driscoll, C., & Cawdell-Smith, J. (2019b). Canine-assisted occupational therapy for children on the autism spectrum: Challenges in do. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 83(four), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619858851

-

Hoagwood, G. Due east., Acri, K., Morrissey, M., & Peth-Pierce, R. (2016). Animal-assisted therapies for youth with or at take a chance for mental health issues: A systematic review. Applied Developmental Scientific discipline, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1134267

-

Jegatheesan, B., Beetz, A., Ormerod, Due east., Johnson, R., Fine, F., Yamazaki, K., Dudzik, C., Garcia, R. Chiliad., Winkle, Chiliad., & Choi, G. (2018). Definitions for animate being assisted intervention and guidelines for health of animals involved [White paper]. International association of human-animal interaction organizations. https://iahaio.org/all-time-exercise/white-paper-on-beast-assisted-interventions/

-

Jorgenson, C. D., Clay, C. J., & Kahng, S. (2020). Evaluating preference for and reinforcing efficacy of a therapy dog to increase verbal statements. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 53(iii), 1419–1431. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.668.

-

Juríčková, V., Bozděchová, A., Machová, One thousand., & Vadroňová, M. (2020). Upshot of fauna assisted education with a dog within children with ADHD in the classroom: A case study. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(vi), 677–684. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00716-x

-

Kanninen, T., Häggman-Laitila, A., Tervo-Heikkinen, T., & Kvist, T. (2021). An integrative review on interventions for strengthening professional governance in nursing. Periodical of Nursing Direction, 29(half-dozen), 1398–1409. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13377

-

Kerulo, G., Kargas, N., Mills, D. S., Law, G., VanFleet, R., Faa-Thompson, T., & Winkle, M. Y. (2020). Animal-assisted interventions: Relationship between standards and qualifications. People and Animals: The International Journal of Research and Do, three(i), 4.

-

Lavan, R., & Knesl, O. (2015). Prevalence of canine infectious respiratory pathogens in asymptomatic dogs presented at US animal shelters. Journal of Minor Brute Practice, 56(9), 572–576. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.12389

-

Liberati, A., Altman, D. Grand., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, G., Devereaux, P., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA argument for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(ten), e1–e34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006

-

Lockwood, C., Munn, Z., & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-assemblage. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13, 179–187.

-

London, M. D., Mackenzie, L., Lovarini, M., Dickson, C., & Alvarez-Campos, A. (2020). Animal assisted therapy for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Parent perspectives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(12), 4492–4503. https://doi.org/x.1007/s10803-020-04512-v

-

Ma, 50. L., Wang, Y. Y., Yang, Z. H., Huang, D., Weng, H., & Zeng, X. T. (2020). Methodological quality (run a risk of bias) assessment tools for primary and secondary medical studies: What are they and which is better? Armed services Medical Research, 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-020-00238-viii

-

Machová, K., Kejdanová, P., Bajtlerová, I., Procházková, R., Svobodová, I., & Mezian, K. (2018). Canine-assisted speech therapy for children with communication impairments: A randomized controlled trial. Anthrozoös, 31(v), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2018.1505339

-

Martin, F., & Farnum, J. (2002). Creature-Assisted therapy for children with pervasive developmental disorders. Western Periodical of Nursing Enquiry, 24(6), 657–670. https://doi.org/x.1177/019394502320555403

-

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(iii), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2012.031

-

Miklósi, D., & Topál, J. (2013). What does information technology have to become 'best friends'? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(6), 287–294. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.tics.2013.04.005

-

Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, Yard., Sfetcu, R., Currie, Grand., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K., & Mu, P. F. (2020). Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In East. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.globalgraag

-

Nagasawa, M., Mitsui, Southward., En, South., Ohtani, N., Ohta, M., Sakuma, Y., Onaka, T., Mogi, K., & Kikusui, T. (2015). Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science, 348(6232), 333–336. https://doi.org/10.1126/scientific discipline.1261022

-

Protopopova, A., Thing, A. L., Harris, B. N., Wiskow, K. Yard., & Donaldson, J. M. (2020). Comparison of contingent and noncontingent access to therapy dogs during academic tasks in children with autism spectrum disorder. Periodical of Practical Behavior Assay, 53(two), 811–834. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaba.619

-

Schuck, S. E. B., Emmerson, N. A., Fine, A. H., & Lakes, K. D. (2013). Canine-assisted therapy for children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19, 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054713502080

-

Schuck, Due south. E. B., Johnson, H. L., Abdullah, M. 1000., Stehli, A., Fine, A. H., & Lakes, Yard. D. (2018). The role of animal assisted intervention on improving cocky-esteem in children with attention arrears/hyperactivity disorder. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 6, 300. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2018.00300

-

Seivert, North. P., Cano, A., Casey, R. J., Johnson, A., & May, D. K. (2016). Animal assisted therapy for incarcerated youth: A randomized controlled trial. Practical Developmental Science, 22(ii), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1234935

-

Silva, K., Correia, R., Lima, M., Magalhães, A., & de Sousa, Fifty. (2011). Tin dogs prime autistic children for therapy? Evidence from a unmarried example study. The Journal of Culling and Complementary Medicine, 17(7), 655–659. https://doi.org/x.1089/acm.2010.0436

-

Stevenson, 1000., Jarred, Due south., Hinchcliffe, 5., & Roberts, K. (2015). Can a domestic dog be used as a motivator to develop social interaction and engagement with teachers for students with autism? Back up for Learning, thirty(4), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9604.12105

-

Tufanaru, C., Munn, Z., Aromataris, E., Campbell, J., & Hopp, 50. (2020). Systematic review of effectiveness. In Due east. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

-

Vitztum, C., Kelly, P. J., & Cheng, A. L. (2016). Hospital-based therapy dog walking for adolescents with orthopedic limitations: A pilot written report. Comprehensive Child and Adolescent Nursing, 39(4), 256–271. https://doi.org/ten.1080/24694193.2016.1196266

-

Wells, A. East., Hunnikin, 50. M., Ash, D. P., & Van Goozen, S. H. M. (2019). Children with behavioural problems misinterpret the emotions and intentions of others. Journal of Aberrant Child Psychology, 48(ii), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00594-7

-

Wijker, C., Kupper, N., Leontjevas, R., Spek, A., & Enders-Slegers, M. J. (2021). The effects of animal assisted therapy on autonomic and endocrine action in adults with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized controlled trial. General Infirmary Psychiatry, 72, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.05.00372:36-44

-

Wijker, C., Leontjevas, R., Spek, A., & Enders-Slegers, Chiliad. J. (2019). Furnishings of dog assisted therapy for adults with autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory randomized controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, l(half-dozen), 2153–2163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03971-9

-

Wohlfarth, R., Mutschler, B., Beetz, A., Kreuser, F., & Korsten-Reck, U. (2013). Dogs motivate obese children for concrete activity: Cardinal elements of a motivational theory of animal-assisted interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 4(796), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00796

-

Xiao, J., Chow, K. Grand., Liu, Y., & Chan, C. W. (2019). Effects of dignity therapy on dignity, psychological wellbeing, and quality of life among palliative care cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology, 28(nine), 1791–1802. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5162

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Stichting Hulphond Nederland.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

C. J. H.: designed the written report, conducted the literature search, analysed the studies, and wrote the manuscript. N. P. S.: assisted in the information analyses, and collaborated in designing and writing the study. R. D.: collaborated in designing, writing, and editing the paper. All authors canonical the final version of the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disharmonize of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits apply, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were fabricated. The images or other 3rd party material in this article are included in the article'due south Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the cloth. If fabric is not included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission straight from the copyright holder. To view a re-create of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Hüsgen, C.J., Peters-Scheffer, North.C. & Didden, R. A Systematic Review of Canis familiaris-Assisted Therapy in Children with Behavioural and Developmental Disorders. Adv Neurodev Disord 6, ane–10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-022-00239-ix

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-022-00239-9

Keywords

- Animal-assisted therapy

- Domestic dog-assisted therapy

- Children

- Behavioural and developmental disorders

- Review

lollistakinquanded1938.blogspot.com

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s41252-022-00239-9

0 Response to "Effectiveness of Animal-assisted Therapy a Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials"

Post a Comment